Uveitis

What is uveitis?

Uveitis (yoo-’ve-i’tis) refers specifically to inflammation of the “uvea” or middle layer of the eye. However, it is commonly used as a general term to refer to any inflammation of the eye. Uveitis is a rare disease. Even the most common type occurs in only 1 person out of 12,000.

To understand uveitis and its treatment, it is easier to think of uveitis as arthritis. Arthritis is inflammation of the joints of the body. The body’s immune system becomes confused and starts to attack or reject the cartilage in the joints of the body, leading to joint damage and loss of function. The only way to prevent this damage is to suppress the immune system with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive drugs. Similarly, in uveitis, the body’s immune system attacks the eye. Unless the immune system is kept in check by the use of either steroids or other immunosuppressive drugs, loss of vision, retinal damage, cataracts, and glaucoma can occur.

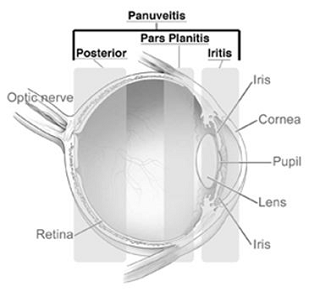

Uveitis is classified by the location. If the inflammation affects the “white” part of the eye, or sclera, it is known as scleritis. If the inflammation affects the front part of the eye, it is called iritis or iridocyclitis. Inflammation that affects the middle part of the eye is known as pars planitis or intermediate uveitis. Inflammation that affects the back part of the eye is known as a posterior uveitis. Finally, inflammation that affects the whole eye is known as a panuveitis.

Scleritis

Scleritis is inflammation of the white part of the eye. It can commonly be mistaken for “pink eye” or viral conjunctivitis. However, scleritis typically causes a deep ache, tenderness, or pain and sensitivity to light that is not present in conjunctivitis. Scleritis can be severe and cause loss of scleral integrity of the eye, even leading to spontaneous rupture of the eye. Additionally, scleritis can frequently be associated with systemic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Due to the possibility of these and other systemic diseases, you may require blood studies and perhaps a referral to a rheumatologist.

Iritis

Iritis or iridocyclitis is the most common type of uveitis, and, fortunately, the most easily treated. It can also look like “pink eye,” though unlike typical conjunctivitis, there is usually more light sensitivity (photophobia) and loss of vision. Sometimes, iritis occurs only once and never returns, but it may recur with frequent flare-ups. The cause of most iritis is unknown. However, half of iritis is associated with a genetic marker, HLA-B27. Those having this marker may be predisposed to develop a systemic arthritis such as ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, or psoriatic arthritis. Treatment is usually the use of steroid eye drops hourly to suppress the inflammation and a “red top” dilator drop to ease pain and prevent the iris from adhering to other eye structures. It is important to remember to shake the bottle to mix the steroid as the drug is a suspension. If you don’t mix it, the drug just sits on the bottom of the bottle with none going into the eye! Additional testing may be indicated if the Iritis persists. Herpes infection of the eye may present with persistent inflammation inside the eye that may require both systemic anti-viral therapy plus steroid eye drops for an undetermined period of time. Usually, in suspected cases the physician may collect a sample of fluid from the anterior aspect of the eye to send to a lab for analysis.

Pars planitis (intermediate uveitis)

Unlike scleritis and iritis, pars planitis does not typically cause a “red eye.” The eye is usually comfortable and pain free. However, vision can be blurred from the inflammation, causing “floaters” (inflammatory cells floating in the middle part of the eye) or swelling in the back of the eye (cystoid macular edema). Most often we do not find a cause for pars planitis. However, it can be associated with conditions such as sarcoidosis, Lyme disease, toxocara, syphilis and multiple sclerosis. The disease tends to flare up and then improve in cycles (waxes and wanes). Thus, we sometimes don’t have to treat pars planitis as the “treatment can be worse than the disease.” If the vision is good and there is no cystoid macular edema, observation is reasonable. If the pars planitis is severe or if cystoid macular edema is present, treatment can consist of an injection of steroids next to the eye (subtenon injection), oral steroids or systemic immunosuppression.

Posterior uveitis

Posterior uveitis comprises the most complex and difficult to manage inflammation of the eye. It also tends to be the most sight threatening. Posterior uveitis tends to be further sub-divided by the cause or by the appearance of the eye. It is very important to work with your doctor as these conditions can sometimes be difficult to diagnose and manage.

Infectious posterior uveitis: Some posterior uveitis can be infectious in nature such as toxoplasmosis, cat-scratch disease, or herpes virus infections (acute retinal necrosis, cytomegalovirus). Treatment depends on the nature of the infection.

Masquerade syndromes: Rarely, cancers, such as intraocular lymphoma, can appear like a posterior uveitis. These diseases mimic uveitis but do not typically improve with steroid therapy and recur rapidly. Diagnosis is important for this group, frequently requiring a vitreous biopsy.

Vasculitis: Inflammation of the retinal blood vessels can potentially be serious by causing a stoppage of blood flow to areas of the retina. Conditions that can cause vasculitis include lupus, sarcoidosis, Bechet’s disease and other diseases. In severe cases, immunosuppressive medicines or an intraocular steroid implant are used.

White dot syndromes: The white dot syndromes comprise a large spectrum of diseases that present with “white spots” on the retina. They are differentiated by their appearance but may be related. The most common complications are cystoid macular edema and choroidal neovascular membranes (abnormal blood vessels growing under the retina). The white dot syndromes include AMPPE (acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy), MCP (multifocal choroiditis panuveitis), PIC (punctate inner choroiditis), MEWDS (multiple evanescent white dot syndrome), and AZOOR (acute zonal occult outer retinopathy).

Autoimmune: Finally, inflammation of the back of the eye may be caused by reaction to your own ocular tissues. These conditions include serpiginous chorioretinopathy, subretinal fibrosis uveitis syndrome (SFU), Birdshot chorioretinopathy (BSCR) and Harada’s syndrome (VKH).

Diagnosis and treatment

Your doctor will probably order several blood tests to determine if you have one of the systemic diseases listed in this brochure. The treatment of each patient has to be customized to control the level of inflammation and reduce the possible side effects. Every form of treatment has potential side effects. Some patients will need regular blood tests to be sure that the treatment medication is not causing problems. It is important to understand that some forms of uveitis are chronic and will need to be treated for a long time, often years. If you have any questions or concerns, please discuss them with your physician.